Add a Little Simon and Garfunkel

I googled Art Garfunkel this morning. I was playing around on the internet, and my random clicking landed me on an article that said that Art Garfunkel had given permission for Bernie Sanders to use his song, “America,” in his campaign ads. I am not personally feeling the Bern, but it made me wonder why Art Garfunkel might be. On his website, I found an interview between Art and Michael Smerconish of CNN where Art says he understands Bernie’s point about the proverbial gap. The one between the rich and the poor. And he said that he just felt like saying, “Yes, you can use my song.” That made me want to listen to “America” and think about all of it. So I did. And then with a choke in my throat, I listened to a few more of his songs, and I remembered things.

Here is the deal with Art Garfunkel and Paul Simon – the two go hand in hand for me – I can’t think about them or listen to their songs without feeling, instantly, every emotion ever known to mankind. My childhood flashes before me, and I am caught in a moment. This happens when I hear John Denver, too. (I grew up in Denver and considered him to be my own – plus once I was skiing in Aspen and found myself in the singles line with John Denver in front of me. He was so short. I thought we would ride on the lift together, but instead he went by himself and I went by myself. I studied the back of his head and hummed “Rocky Mountain High” and “Poems, Prayers, and Promises” the whole way up).

Every song on Simon and Garfunkel’s Greatest Hits comes complete with a very specific childhood memory for me. For example, when I hear “Cecilia” I am instantly transported to the Alpine Ice Arena off 1-25 in southeast Denver. It is 1974, “Cecilia” is blasting on the sound system, and I am wearing a horrible Geranimals type of outfit: pink checkered, collared shirt and polyester pants. I am cold, but in an “I feel so alive” sort of way. I can see my breath as I work on my sit spins. The double time beat, hammered out on the refrain,

Cecilia, I’m down on my knees . . .

I am skating back crossovers and turning into my spin.

I am begging you please. . .

I sit on my left butt cheek and extend my right leg out straight and I rotate two, three, four times.

. . . to come home. Come on home.

I fall out of the spin and slide on to my side and feel the cold, hard ice on my arms and hands. Then I roll over and stare at the ceiling for a moment before I get up and try again.

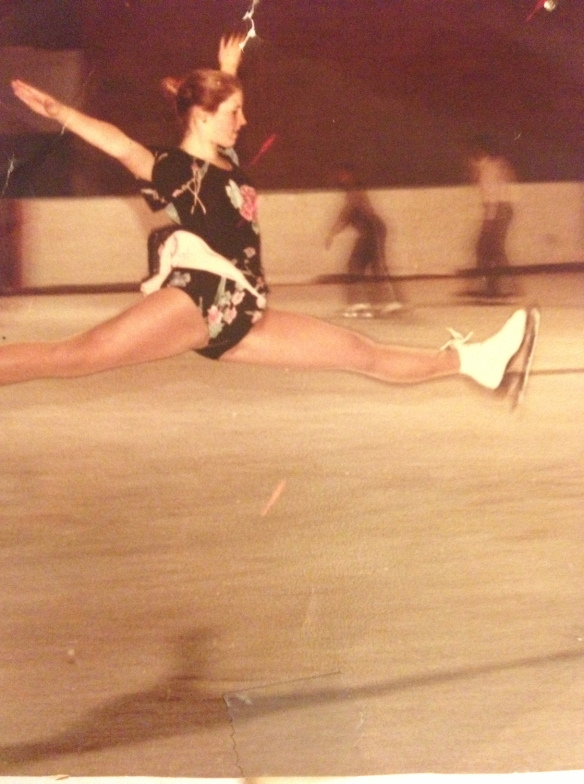

“Cecelia” is a song about an untrustworthy lover, but for me it means gold medal dreams and Dorothy Hamill haircuts. “Cecilia” doesn’t mean “making love in the afternoon,” it means trying on those fancy skating dresses in the club shop and watching the burly hockey players crash into the rink walls. “Cecelia” means my sister’s commitment to figure skating that took her to state and regional competitions. It’s my parent’s pride and joy. It’s my best supporting actress to my sister’s starring role. It’s me. Trying, failing and quitting, there at the rink.

And then there’s “Scarborough Fair.” The original song was an old English ballad that can be dated back as far as 1670. The meaning wasn’t exactly clear to me, but the words seemed current when I used to sit on the living room floor and play that song over and over on my parent’s turn table. Our stereo system sat right on the gold shag carpet. Apparently we didn’t have shelving or a cabinet to hold everything. I flipped through my parents’ Kingston Trio’s and their Nat King Cole’s and their Shirley Jones’ Show Tunes that leaned against the wall, and I pulled out Simon and Garfunkel.

She once was a true love of mine.

To me, true love was as uncomplicated as staring dreamily at the album cover. Paul looked peculiar in that funny hat. Art was the handsome one. His sparkling blue eyes trumped his fluffy hair. He looked like a real man to me.

I liked how the vinyl record was encased in a thin, rice paper sleeve. I held it carefully by the edges and treated it like a newborn baby. I remember gently setting the needle down on the exact spot on the record where “Scarborough Fair” started, and I made sure not to scratch it. Then I listened and imagined if I would marry a real man one day, an honest, hard-working one. A true partner. The Simon to my Garfunkel.

Parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme.

And the words smelled so good.

Recently, my sister was over for dinner. I made my chicken and vegetable soup. She wanted the recipe. “It’s easy,” I told her. Then I described how I simmer the chicken in broth for about an hour and then add the carrots, celery, onion, and garlic, and quarter cup each of barley and wild rice. “And after about another hour,” I said. “Throw in some salt and pepper and add a little Simon and Garfunkel.” She laughed. She knew exactly what I meant.

Conversely to my associations with “Cecilia,” listening to “I am a Rock” back then made me feel like I was a part of the world outside of my own little existence. I knew what they meant when they said,

A rock feels no pain. And an island never cries.

I was a fourth grader. How did I know that? Maybe I knew it because that year my father’s business failed, and my mother went to work for the first time in her life. For me, it meant that my little brother got shipped off to day care, and I came home after school to an empty house. I ate my snack by myself and waited for someone to get home. I wanted to be that rock and that island.

My teenaged daughter listens to “The Boxer.” It is one of her favorite songs. But for her, it’s Mumford and Son’s version. I have to explain to her how Simon and Garfunkel’s original version is different. Even though I love Mumford, I tell her how Mumford’s version leaves out the part that means the most to me. Simon and Garfunkel follow their “lie-la-lie” with a crash of the cymbals, and my heart skips a beat. Mumford doesn’t do that. I ask her what it is about the song that she likes.

“The banjo,” she says. “And the message.”

“What message exactly?” I ask.

“The message where he remembers every gloved hand that cut him, and he wants to leave that behind, but the fighter still remains. It’s that he always remembers his past but grows from it and moves on. I like that message.”

Yeah. I like it, too.

Asking only workmen’s wages, I come looking for a job, but I get no offers.

Is that what’s happening out there in the wild world I wondered when I was a kid. Today I sing the words, I hear those cymbals crash, and I feel the weight of life’s struggles. I can pinpoint the disappointment and the devastation. I wonder what meaning this song will have when my daughter listens to it when she is my age.

I was just a tot when Simon and Garfunkel were making it big. Art Garfunkel says that it was the second half of the sixties when everything happened for him. A mere five years. I was six years old in 1970 when he and Paul were already going their separate ways. Lucky for me, and all of us, that when the brilliant truth is recorded on vinyl (or CD or whatever), we get to remember and learn something every time we play it back.

On his website, Art Garfunkel says that he wanted his song, “America,” to be “urgent, reaching, yearning, shining, and full of glory for my love of America.” Mr. Garfunkel, all of your songs represent that for me in one way or another. Your songs are a scrapbook of my American childhood. And I am moved. I am moved because I yearn for the marvelous parts of my childhood that are gone. I am moved because I can feel the residue of past sorrows as well. I am moved because I worry whether or not I gave my own kids the best childhood possible. I am moved simply thinking about the future of all childhoods.

I’m empty and aching and I don’t know why.

“America” brings up a longing for something lost as well as for hope that something better lies ahead. For me, it also stirs up gratitude. Mr. Garfunkel, I will simply say thank you. I’m OK with your giving the song to Bernie Sanders. Because you gave this song to all of us. And maybe when we

. . . all come to look for America,

we will find it.

Still here. Still home. Still full in our hearts. Even in these uncertain times.

–

P.s. I’ll be thinking of you when I go see your old pal at the Berkeley Greek this June. Wish you would be there, too. But I understand.

My sister, Laura, at the end of her competitive figure skating career. Circa 1979.