Helicopter Parent, Helicopter Child

When my son was a senior in high school, he accused me of being a helicopter parent. He did it by sending me an email with a description of the official term from one of the books in his psychology class. In the subject line of the email he wrote: This is you!

Here is what was in the email:

“Helicopter parenting means being involved in a child’s life in a way that is over controlling, overprotecting, and overperfecting, in a way that is in excess of responsible parenting.”

I was outraged. This was my reply:

“I AM NOTHING COMPARED TO ALL THOSE OTHER CRAZY PARENTS OUT THERE!”

Helicopter parent. Please. Just because I worried constantly about his whereabouts, asked him repeatedly about his grades (and then checked them online regardless of what he said), drove more carpools than a city bus driver and went to decade’s worth of parent club meetings (until I was completely burned out), did not mean I was a helicopter parent.

However, now that my son has graduated and moved across the country for college, and my daughter is right behind him, I look back on all of it and wonder. If you compared me to my own parents, especially my father, I was definitely a hoverer. And on a recent spring break trip with my mom and dad, I discovered that if I was a helicopter parent, then I am also a helicopter child, hovering over my aging parents.

******

I love reminiscing about the free-wheeling days of my 1970’s childhood. My dad no sooner knew what time school started or what essays were due in my English class than he did what boys I liked. But that is not to say that he wasn’t an involved parent, because he was. He went to all my skating shows, flute recitals and soccer games, taught me how to change a tire, grow green beans in the back yard and balance my checkbook. And my mom, she was amazing. But until very recently, she had no idea that at Cherry Creek West Middle School in Englewood Colorado, I had a 6-pack of powdered sugar mini-donuts and a REGULAR Coke every single day for lunch.

A key example of the difference in their level of involvement in my life and my level of involvement in my own kid’s lives is this: my parents didn’t get a blasted email every time someone sneezed at school! In my opinion, today’s parents have been completely set up for judgment.

******

When James was barely 5 and Julia was pushing 4, I took them skiing with my father. I was already divorced, and taking the littles skiing by myself was nearly impossible. But when my dad was in his sixties, he hit the slopes on his own every now and then. One sunny Saturday, the three of us were able to join him.

In the morning, I put both kids in tiny tot lessons and skied with my father. After lunch, Julia and I wrangled with the rope tow while “the boys” took the chair lift to higher, more advanced adventures. Later, at our designated meeting point, Julia and I stood, faces to the warming sun, and watched and waited for dad and James to ski down the mountain. As my father approached, I grinned widely, grateful for this day with my kids and my father. I anticipated James, in his bright green, red and blue ski jacket, sliding up behind dad and skidding into place. But as dad got closer, I couldn’t see James anywhere. My grin fell off my face and my heart pounded.

“Hi Sweetie,” dad said as he stabbed his poles into the snow next to me.

“Where’s James?” I belted out.

“Oh, he wanted to go up again.”

“What?” I shrieked. ‘’Where is he?”

“Well, on his way up, I guess.”

“Oh my God, dad! He can’t go by himself!”

“Sure he can. You kids did it all the time.”

I side stepped quickly up toward the chair lift, scanning the line for James’s bright jacket. Nothing. My thighs burned as I focused on the lift hut, thinking he might be getting on the chair. But I saw only teenagers and families and old people. Oh God, I thought. This is bad.

Then I saw him, several chairs up the lift, sitting by himself, looking over his shoulder, his poles in one hand, his other hand waving at me joyously.

“Jesus, James. Hold on!” came screeching out of my mouth.

I was frozen. And in a matter of seconds he was gone, over the horizon.

Should I have been surprised that my dad allowed this to happen? No. My dad’s nickname was “Fun Guy Bob.” His motto was, “We Aim to Please,” which, during my childhood, meant, “Ask, and Ye Shall Receive.”

“Dad, will you please take me to Baskin Robbins?” Note that I rarely asked my mother.

“Well, sweetie, that sounds delicious.”

“Dad, can we get gerbils?”

“If you think you can take care of them.”

And when I got a little older and my dad was well into his career as a mechanical engineer at Coors Brewery in Golden, Colorado,

“Dad, do you mind if my friends and I have some of the Coors Light that is stacked up in the basement?”

“Fine with me, sweetie. But, remember, everything in moderation.”

I am 98% sure we did not drink the Coors Light in moderation.

James’ solo ride on the lift that day became an analogy to pretty much his whole life thus far. And I can’t help but wonder if the times he spent with my dad helped to build his confidence. In the meantime, I spent 18 years analyzing parenting books, agonizing over playground discipline, forcing bedtime schedules, coordinating hot lunches at middle school and being team mom, parent rep and God knows what else.

My daughter is now a senior and will graduate next month. I don’t care anymore if anyone calls me a helicopter parent. The deeds are done and it will all turn out the way it is turning out. And, it seems, all those skills I acquired helicoptering my kids are now transferrable.

******

This past spring break, I took a trip to Europe with my daughter, my sister, my niece and both my parents. We were to embark on an 8-day river cruise on the Seine after two days on our own in Paris. My mother is 73, and my father, who is 77, is being treated for the beginning stages of Alzheimer’s. My mother was certain that this would be their last adventure in travel and convinced me that my dad would be just fine on this trip. But before we even boarded our flight in San Francisco, I had a feeling that it was all a bad idea.

“Bob, where is your raincoat?” My mother asked him.

“Bob, you forgot to comb your hair.”

“Bob, did you take your pills?”

It was torture. But what happened when we arrived in Paris was the final straw that made me see the gravity of his failing short term memory. After we checked in at our hotel, we went to the bar to have our café au laits and pain au chocolates before our first outing to the Musee D’Orsay. My father looked over his menu and said with utter frustration, “This is all in French.”

“Dad,” I said laughing, so as not to cry, “we are in France.”

“Oh, right,” he said, reconsidering his menu and then laughing along with the rest of us. Luckily, my father’s issues have not changed his underlying Fun Guy Bob personality. But it was at that moment that I put the keys in the ignition of my helicopter and cranked up the motor. I waited for the hum and the “pht, pht, pht,” of those blades, spinning faster and faster, until I lifted up and hovered directly over my father, and I stayed there, to the very best of my ability, for the entire trip.

“My father would like the cream of cauliflower soup and the beef tenderloin, medium-well, s’il vous plait,” I say to the waiter.

“My father is having trouble with his audio set,” I say to the tour guide as I fiddle with his earpiece and try to get it to stay in his ear.

“Stay with Pops and don’t leave,” I say to my daughter as I run back to our room to get my scarf.

At one point we lost my parents. We were in Giverny, and it seemed that I had temporarily parked my helicopter on one of Monet’s lily pads. A frantic “kid lost at the zoo” scene erupted, with my sister searching in one direction and me in another while our tour guide called the other tour guides with an all-points bulletin. We found them eventually, waiting at the bus.

“I couldn’t remember the meeting spot,” my mother said.

I shouldn’t have let go of her hand, I thought, confusing my mother – with my daughter – with my niece at Chuckie Cheese years ago.

Immediately upon our return home, my mother had to attend a funeral in Pasadena. She planned to fly from Reno, where she and my dad live – my brother, Rob, and his family live there, too.

“I’m just going to leave dad for one night,” Mom said to me on the phone before her trip. “It will be better if I go by myself.”

“MOM, ABSOLUTELY NOT! YOU CANNOT LEAVE DAD ALONE BY HIMSELF OVER NIGHT!” My stomach hurt as I pictured my dad wondering through the house alone.

“It’s fine. Your brother will check on him.”

“Mom,” I said, trying to be calm, trying to watch my tone, trying to have impact. “You don’t get it. You can’t see that this is not a good idea. What if he wakes up in the middle of the night and can’t remember where you are?”

“Well, I didn’t think about that.”

“Mom, he looks for you everywhere. He can’t be alone.”

“Ok,” she said. “Maybe you are right.”

Long story, short, my brother stayed with my dad, and I felt the kind of relief that you feel when your five year old boy comes whizzing down the slope after having been by himself on the mountain, for exactly 34 minutes, while you waited, pretending that you were not terrified, and he skids up to you, red cheeked and wild eyed and wraps his puffy-jacketed arms around your waste and says, “Mom, that was so much fun!” It was that kind of relief.

Maybe it’s just in my nature to take charge. Or maybe it was because I suddenly became hyper aware of the toxic fog that my mother was living in. It was part exhaustion and part denial. It reminded me of myself at times, trying to figure out the right thing to do for my kids. When we see that the outcome might not be desirable or that it might even be tragic, we get in there and try to take control. I don’t know if I was or was not a helicopter parent to my children. I do know that I did whatever I could to try to put the odds in their favor for successful outcomes. I didn’t write their college essays or go with them to basketball or badminton practice, but I did make them do their homework and write thank you notes and ask them to consider what they want their own lives to look like. I have come to the conclusion that labeling someone as a helicopter parent is all relative.

“Text me when you get there.”

“Text me when you leave.”

“Do NOT text me when you are driving.”

This is what I now say to MY PARENTS!

I know that there is a difference between raising children and caring for aging parents, and clearly, Alzheimer’s related issues are serious. But our actions and re-actions all come from the same desire: we just want the best for them. If I am a helicopter parent, then I am OK with that. And I am comfortable being a helicopter child, too. And now, as I just spent two whole minutes trying to come up with the word for those metal blades that go round and round on the top of a helicopter to help it take flight, I am hopeful, that when and if I ever need it, one of my children will fire up their propellers (there’s that word) and hover over in my direction.

Giverny, 2015. Dad, Lisa, Julia, Kellie, Mom

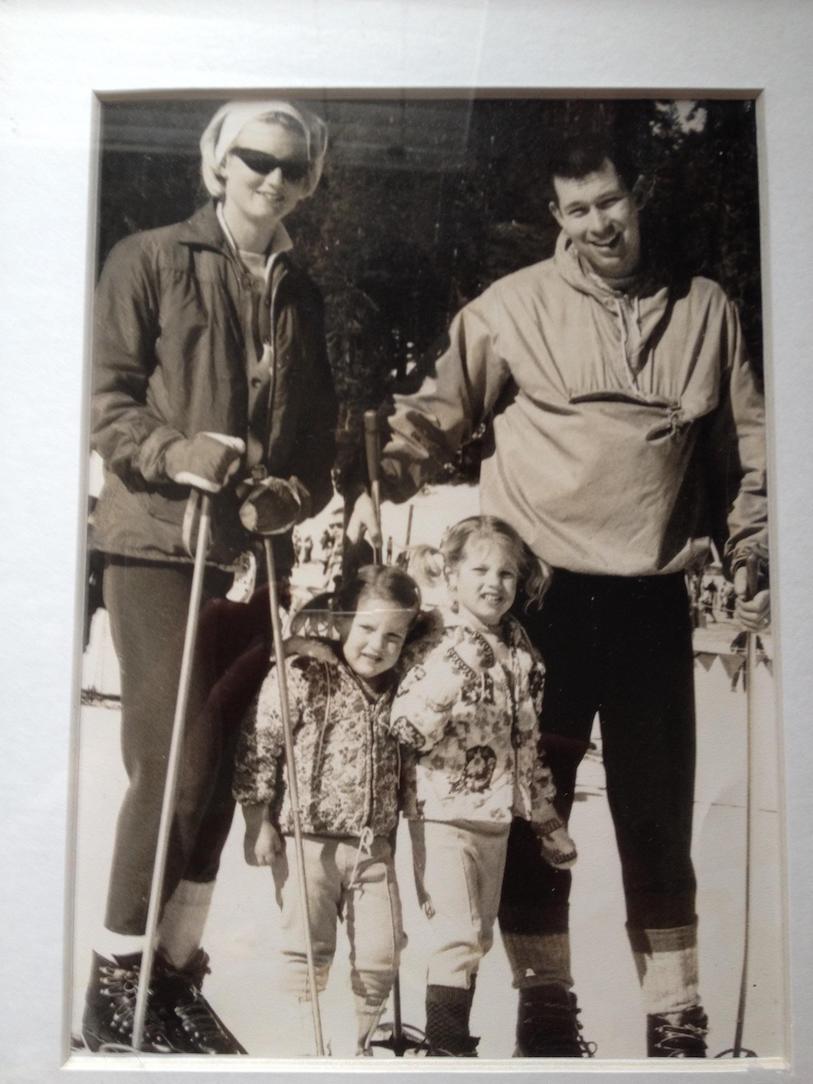

Squaw Valley, 1967. Mom, Lisa, Laura, Dad.